On display: black twisted steel bent to resemble scrolls, welded to spindly round metal stock and labeled wrought iron lawn furniture. Nearby, a wrought iron grille. After so many centuries, a metal once commonplace and used for bridges, buildings, stream locomotive boilers, farm machinery and many other applications where steel is used today has been relegated to a label for lawn furniture. Actually, this twenty first century wrought iron lawn furniture is wrought steel. Real wrought iron, the metal, was last produced in large quantity around the late 1960s.

I first encountered wrought iron while working for the Calhoun County Historic Bridge Park restoring nineteenth and early twentieth century riveted truss bridges. Steel is a metal I worked with (for over thirty five years), fabricating it into welded assemblies for bridges and buildings and teaching people how to weld it. My approach to the restoration of these historic metal truss bridges was as a steel fabricator, but I soon realized the metal I was working with had some unusual characteristics. Looking at a piece of steel and a piece of wrought iron alongside each other they appear to be the same, the same weight, the same feel. It’s their internal structure that makes these metals so different.

Journey of Discovery

Wrought iron in the early twentieth century was still considered to have a future because of its unique qualities. From the preface to the second edition of the A.M. Byers Company’s handbook (1939) Wrought Iron: Its Manufacture, Characteristics and Applications:

“During the past decade there has been a rapidly growing demand for wrought iron in many different products. This demand has been accompanied by a need for information on the qualities of the material and their application to present day problems.”

It is surprising that a metal widely used for centuries was so soon forgotten by many in the engineering and industrial fields. Although wrought iron is no longer found in recent construction, wrought iron structures are still in use today and knowledge of the characteristics of this metal important for preservation.

In my work on century old metal bridges, preservation of wrought iron became an educational journey of discovery through books and articles. With the benefit of having skills in steel fabrication and in teaching welding, I developed an appreciation for this unique metal. Several books provided valuable information in the manufacture and use of wrought iron and an introduction to the iron-maker’s language of the puddling furnace: the “pig boiler,” “puddlers’ candles” and “rabble” and the processes of “thickening the heat,” “coming to nature” and “rolling the bloom.”

Wrought Iron: Its Manufacture, Characteristics and Applications [by Consulting Metallurgist J. Aston & Chief Metallurgist E. B. Story. (1939). Pittsburgh, PA: A. M. Byers Company]

An Introduction to the Metallurgy of Iron and Steel [by Professor of Metallurgy H. M. Boylston. (1936). London: John Wiley & Sons]

The Iron Puddler [life story by iron puddler J. J. Davis. (1922). New York, NY: Gossett & Dunlap]

Wrought Iron

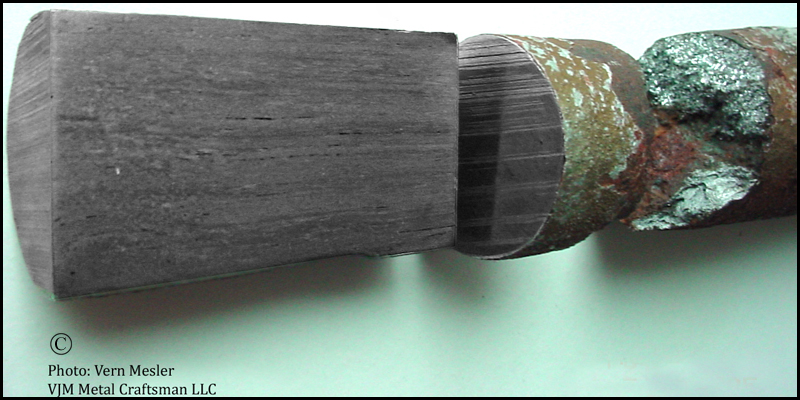

“Wrought iron is best described as a two-component metal consisting of high purity iron and iron silicate a particular type of glass-like slag. The iron and the slag are in physical association, as contrasted to the constituent of other metals. Wrought iron is the only ferrous metal that contains siliceous slag.” (Aston & Story)

Wrought iron was produced in a hand-puddling furnace, and the worker who manned the furnace was called a puddler. “The quality of the wrought iron produced in the hand-puddling furnace was directly proportional to the skill of the puddler and beyond that skill no scientific control was possible.” (Aston & Story). It took exceptional observational skill and physical ability of the iron puddler to produce (with his helper) 800 pounds of quality wrought iron in less than two hours. In an effort to compete with low-cost steel being produced in the early twentieth century James Aston, consulting metallurgist for the A.M. Byers Company, began researching a method to produce large quantities of wrought iron that permitted quality control of production and refinement of the wrought iron that was not possible with the hand-puddling furnace. What became known as the Byers Process was used for wrought iron production until the company closed in 1969.

Preservation of Wrought Iron

It is essential that those responsible for the preservation of wrought iron recognize the significant distinction between wrought iron and other metals. Recommending preservation procedures best suited for steel or cast iron rather than wrought iron could result in damaging or destroying an irreplaceable historic metal. Electric arc welding has been used successfully in the repair of wrought iron, contributing to the preservation of much of the original metal, as recommended in the Secretary of Interior Standards for Rehabilitation. The Welding Institute (check link) has good recommendations for the repair of wrought iron and provides welding procedures and electrode recommendations.

(hold text) Another relevant source is Evaluation and Repair of Wrought Iron and Steel Structures in Indiana by Mark D. Bowman, Professor of Civil Engineering at Purdue University.

The Artist and Wrought Iron

To illustrate the distinctive characteristics of wrought iron, I asked the artist blacksmith John Logan of Leslie, Michigan, to create a metal sculpture from a section of 1880 wrought iron. Logan’s wrought iron sculpture had two distinctive elements in its creation, the actual finished piece and Logan’s description of crafting the sculpture to highlight the unique characteristics of this metal. I described Logan’s work in the December 2010 Craftsman’s Newsletter.